- Home

- Elizabeth W. Garber

Implosion Page 4

Implosion Read online

Page 4

“Wow, Dad, it will be twins with our house,” I said. Our home was the only other building so far built with these panels. “That is so groovy.” I was trying out the new hippie expressions I heard on the radio.

Dad rolled his eyes, “Groovy?” We both laughed.

AFTER DINNER, AS my brothers helped my mother wash dishes, my father put on a new Dave Brubeck Quartet record and settled into his black leather Eames chair with a pad of paper and pencil. I curled up in the orange Womb chair with Vogue, each of us reflected in a spotlit island of light on the dark opaque walls behind us. The long room ended in bookshelves on either side of the white stone wall with a fireplace. My father had placed theatre spotlights on the ceiling to shoot beams of red, yellow, and deep blue through the hanging Bertoia sculpture. Colorful shadows moved across the white stone wall and the bullfight painting. Circling the entire room high above us was the continuous gleaming stream of red. At the other end of the long room, in the kitchen, my mother wiped down the Formica counter. The grain in the plywood walnut cabinets moved in patterns.

Brubeck’s friendly piano circled the room, punctuated by Paul Desmond’s lilting sax, with a deep bass and steady drums in the background. Dad leaned back, reading liner notes on the album. He called out comments. “Would you listen to that!” My dad had taken me when I was a little girl in pajamas to see them at a club. I’d grown up playing their red plastic 78s. Listening to Dave Brubeck was my best lullaby.

My mother and brothers played a card game at the kitchen table. The music was a lively stream flowing around all of us in that big room, tucking us in with its syncopated rhythms. I looked around the room and imagined students living in a modern tower, with glass walls reflecting them as they hung out in lounges on chairs like ours. They would learn to be Modern, like I had.

My father sketched the dormitory layout, made notes, and murmured to himself, “It will be a perfect building. They’ll just love it.”

Villa Savoye à Poissy, photo by the author, 1973

VILLA SAVOYE

1967

The business of Architecture is to establish emotional relationships by means of raw materials.

—LE CORBUSIER

MY FATHER AND I LAID OUT OUR MATERIALS AND tools on the long built-in desk in front of the window that ran the length of my parents’ bedroom. He’d always said you can never have a big enough desk. We were working on my end-of-the-year eighth grade French project. Some kids were making French bread, or a model of the Eiffel Tower out of toothpicks, or cheese fondue. We were building an architectural model of my favorite building by the French architect, Le Corbusier: his Villa Savoye.

At the architectural supply store I had spent my entire babysitting savings of thirteen dollars, earned at $0.50 an hour, on basswood dowels, white mat board, special glue, gray rough-textured sandpaper for the driveway, and a bag of green lichen to glue on the board at the end to appear to be grass surrounding the house. Over years of visits to my dad’s office, I’d seen many scale models. I couldn’t believe we were making one together.

For years when my mother ran errands downtown, she would drop me off at dad’s office in a tall brick house with a small round tower near the University. I’d climb the long carpeted stairway, holding onto the carved banister, before entering the bright white drafting room where angled tables, like boats with sails, flew above my head. Long wooden T-squares, clear triangles, and mechanical pencils littered vast sheets of paper, covered with lines, tiny arrows and careful printing in pencil. I’d sniff the sharp ammonia from the blueprint machine in the next room.

On one occasion, I slipped through a circle of men to find my dad gazing at a roll of blueprints. He’d picked me up so I could sit on a tall stool and see the heavy roll of paper they were studying. He pointed with his finger as he talked. Then he looked at me.

“Lilibet, see if you can help us out. What do these double lines signify?” His voice was warm and booming. I squinted down at the grid of blue lines, my face serious.

“Those are walls.”

“And what are these cross lines?”

“Windows.” I could feel the young men in their white shirts, sleeves rolled up, smiling as they watched me, Woodie Garber’s daughter. And I could feel the pressure of the history of architecture in my family weighing on me.

“Good. And this?” I peered at a series of parallel lines and suddenly I wasn’t sure. I could feel my father’s held breath, his steady eyes, and in my own eyes, the sting of tears. I had to know the answer. I had to prove myself to my father.

He made a little movement with his fingers, like a little person climbing steps, and I knew in an instant. “Those are stairs going down to the next floor we can’t see!”

He patted me on the back with his big warm hand. “That’s my girl!”

Over the years I absorbed their language of special words: clerestory, cantilever, reinforced, transparent. I loved the names of architects they murmured reverently: Walter Gropius, Mies van der Rohe, Alvar Aalto, and my father’s favorite, Le Corbusier, whom he called Corbu. Le Corbusier’s complete works, a series of white books, were placed prominently on a bookcase next to my father’s desk in his private office.

As the years passed, I’d make a bee line to sit on the metal Bertoia chair next to Corbu’s books. Bertoia said his chairs were mainly made of air. My father was the first architect to commission Bertoia’s sculptures to go with his buildings.

I’d turn pages in a Corbu book, looking at old photographs of white buildings and drawings. My father would pause between phone calls to stand next to me, pointing to a photograph or drawing, admiring details of a line of windows, a curving roof garden.

Every year there were architectural scale models of his newest projects. I walked around the model for the proposed Cornell University Library on a large table next to the window. My father came over and crouched down so he could look at eye level with me. I peered in the little windows and doors, touched the pretend trees and scratchy bushes. Tiny faceless people walked on sandpaper sidewalks, looking like they knew where they were going. Two long walls were covered by an attached sculpture by Harry Bertoia, a jigsaw puzzle of colorful panels. My father pulled shades down over the windows and turned on a light inside the model. I imagined being a student going to the library at night, looking through the trees at warm window light glinting through the red, blue, and yellow panels on the sculptural wall.

My father explained to the students standing next to him. “They loved the design but they didn’t want the sculpture attached to the length of the building. But that Bertoia sculpture was absolutely key to the whole design. I told them, ‘No way. You take it as it is or you leave it.’”

I turned to look up at him as his voice grew more forceful. “Never!” his voice punched and his eyes pierced. I was a little afraid because he sounded so angry. “Never capitulate or change your concept to meet design-by-committee!”

My father launched into one of his lectures. “Some people are so damned narrow-minded and are afraid of modern architecture.” Then he eyed me. “You know you don’t use swear words!”

I nodded yes. I knew that.

He said so many people in America wanted buildings that looked like Greek temples or brick palaces, monuments on pedestals. He loved what was clean, clear, and elegant. He said, “What happens inside the building must determine the shape of the building. A building should support how people live inside it, not control how they live.”

I listened carefully, intent on becoming his finest student. I went back to the white linen book of Corbu’s buildings. When I was eight, I showed my father my favorite, a house that looked like a sculpture of light and shadow set in a meadow.

He pronounced the French name for me, Villa Savoye, near the town of Poissy. “You are something special, Lilibet. It’s my favorite, too.”

I leaned against him and he put his arm around my shoulder as we gazed at the photographs.

I loved sharing architectu

re with him. I was usually stranded in a world of chatting children and practical mothers. I longed for the importance I felt when the intensity of his attention beamed on me like a spotlight. Most days, I was a quiet, awkward girl who helped her mother and told her brothers when to pick up their cars. But with him, I entered another world. The two of us enjoyed discussing the colors Bertoia chose to paint on square discs on the sculpture hanging in front of the stone wall in our living room. My mother might look at a Kandinsky abstract lithograph my father had bought during the Depression, and ask awkwardly, “Is that a boat in a storm?” In contrast, father and I would glide like figure skaters, effortlessly discussing the play of texture and intensity in the lines and spaces. I became fluent in my father’s languages, yet away from his world I floated adrift, often unable to speak with other kids on the school bus. Standing in the sun on a baseball field, I was the gangly girl who was teased for never catching the ball. A desperation and yearning built in me for his company, his conversation, his attention.

I was enthralled, charmed, and captivated by my father’s world, his mind and his affection. But to be in thrall comes from the Middle Ages: to hold in slavery. Being enthralled locked me to him.

As we started building the architectural model, it was much more complicated than I had imagined. My father said, “First we line up all our tools so they are ready to use.” I already had my own half-size drafting board, t-square, clear plastic flat triangles, mechanical pencil, and a professional metal compass with little tubes of replacement lead and metal points. When I was in fifth grade and we still lived in the old Victorian house, I’d asked my parents for a compass for Christmas. I didn’t explain I wanted to know how to find my way if I was lost in a forest.

My father had assumed I meant a drafting compass and bought me a complete beginner’s set of drafting tools. On Christmas morning, when I opened the large pile of unusually shaped presents, I was thrilled. Now I could draw plans like my father.

“Anything you draw,” he said, “I’ll take to the office and bring you home blueprint copies.”

After Christmas dinner with our aunts, the bald uncles, and older cousins, I showed them my drafting compass with pointed legs. But I confessed, I didn’t know how to tell directions with it. This brought great gales of laughter, becoming a story to be repeated as a joke on my father.

My father had taught me that Christmas day how to use my drafting compass on transparent graph paper. Pinching the compass lightly at the top, he touched the point through the paper until it pierced the wooden drafting board. He twirled the compass which pirouetted like a ballet dancer, one long thin leg pinned to the board and the sharpened lead toe stretching in a circle across the page. We drew a compass flower, with intersecting circles that etched five identical petals. I spent all of Christmas leaning over my drafting board, teaching my wobbly dancer how to twirl in circles until my technique became as precise as my father’s. I glanced up at my father in his red and black plaid shirt and knew he was happy that I loved my presents.

By the end of the afternoon I announced to him as he leaned back in his Eames chair, “I want to be an architect too.”

His face darkened. “I wouldn’t wish that on anyone, especially you, Sugar. It’s just one battle after another. You have to fight for every goddamned inch of progress you make in a town as narrow-minded and conservative as this one. I should have become a lawyer for all the fighting I’ve had to do in my life.” He shook his head at me and his adamancy silenced my ever thinking of being an architect.

NOW, AS MY father and I set out additional tools he’d brought home from his office, I felt serious and important. His father’s triangular scale ruler looked like it was made of ivory, with little lines and numbers along each edge. A sharp X-Acto knife for cutting mat board. Drafting paper and the white book in French with Corbu’s plans. “First,” he said, “we have to decide what scale model we want to make.” He showed me the scale on the side of the paper, and turned his trisquare so it would measure centimeters. “Because the building is French, the designs are in metric scale. A hell of a lot easier to deal with than our inches, which are a pain in the butt, if you excuse my French!” He laughed as he calculated on a scrap of paper what scale we should use.

We decided that the model should be roughly about one foot square on a two-foot-by-two-foot piece of plywood. I picked up my compass and twirled it on the board. I said, “I guess we won’t need this today, building a square house.”

He smiled. “We sure do need it! Look again.” He pointed to a curved round wall on the ground floor, and then to a tiny circle with lines.

“What’s that?” I asked.

“It’s a spiral staircase, running up through all the floors.

You can stroll up the ramp or climb up the spiral steps. It’s really quite elegant. You’ll see.”

I leaned against my dad’s shoulder as he plotted out the dimensions of the ground level of the house on the plywood base and explained the design.

The pilotis were metal posts that supported the structure. My father explained, “Corbu revolutionized how we think about exterior walls.” If the posts carried the weight, walls could become nothing more than a skin over the building with cut-outs for windows, allowing a building to feel light and open. From round dowels we cut posts with the X-Acto knife and glued them in a grid, equally spaced, five posts in five lines, forming four cubes by four cubes for a square house.

It was a house designed for the modern age. “You drive up to the house and straight into the garage,” he said. His fingers pretended to drive a car under the house, and turn into the garage. I imagined my father’s new XKE Jag pulling in, snug in place, a sleek modern design that matched the house. His two fingers walked like little people getting out of the car and ascending the ramp into the middle of the house.

He asked, “Do you remember some of Corbu’s principles for Modern buildings?”

I offered tentatively, “Make a house a Machine for Living in and Form follows Function?”

“Good girl, exactly!” He nodded, patting my arm, but he corrected me. “Not many people remember that Louis Sullivan, the grandfather of modern architecture, said ‘Form ever follows function.’” That’s one of the reasons my father hated Frank Lloyd Wright. “Frank Lloyd Wrong in my book,” he said. In my father’s view, Sullivan taught Wright everything and Wright had not honored his teacher. “But don’t get me started on that!” he’d say.

He ran a hand over his bald head. “Once you get your car out of view, and come up the ramp, what do you see?” He swung both arms out in a sweeping motion. I walked my fingers onto the second floor garden of our model where it opened to the sky. Thin walls enclosed the house inside and out like white ribbons, with strips of windows that framed the meadow, woods, and Paris in the distance. He said, “You live above the cars or roads.” Looking out my parents’ bedroom window, my line of vision went straight over the driveway below to our vegetable gardens and trees, where clothes that hung on the line were drying in the wind. The land around our house was still raw, weeds rising out of bulldozed earth where it would eventually be landscaped with ground cover, lawns, and gardens.

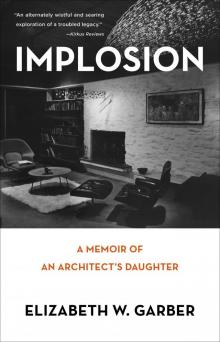

Garber house, 1966

I could see the principles he had applied to our house: the garage below, the house cantilevered out on posts, an open plan of rooms, and exterior and interior spaces under the same roof. The structure was divided into equal sections by posts approximating the geometry of Villa Savoye. We parked the sports car and VW bus in the basement, the hardworking part of the house to be used for practical things. A Machine for Living in.

Our chest freezers were stocked with corn, peas, string beans, strawberries, and applesauce. The wine cellar built into the earth kept the dusty bottles cool, and the root storage room was lined with bushels of potatoes, onions, apples. The shelves were laden with home-canned tomato sauce, stewed tomatoes, relish and pickles, golden globes of peaches in syrup, and rows of jams and marmalade. The vast room of the

garage was divided into sections for storage units, carpentry shop, tractor, and gardening tools. With the functional spaces hidden underground, the living space floated above like a sculpture of light and shadow surrounded by gardens, a Machine for another kind of Living.

Villa Savoye was a square divided into a grid of sixteen squares, roughly sixty feet by sixty feet. I asked my father, “How many posts do we have in a row on each side of our house?”

“Think about it.”

On either side of the Great Room was a pair of long porches, each edged with three white posts, equally distanced, with an overhang at the end, just like Villa Savoye.

I had to figure this out. I ran out of my parents’ room, past the galley kitchen into the Great Room.

I called out, “Where’s a tape measure?”

“In the tool drawer. Make sure you put it back!”

I grabbed the measure, followed the glass wall to the heavy wooden front door. Outside, the earth smelled warm from the spring rain. At the edge of the porch, the decking was wet under my bare feet. I measured from the middle of one post to the next. Thirteen feet and a few inches. I ran down the stone stairs to the entry area under the overhang held up by another post. I measured from the pilotis to the wall of the house, about thirteen feet. I measured the first bay of the garage. Thirteen feet again. I walked across the gravel driveway. I looked up at the line of four bedrooms. In the end room above me a spotlight shone on Daddy’s head as he leaned over the model, gluing pieces into place. Each bedroom section was the same, four in a row, all about thirteen feet wide. So our house was a grid of four sections by five sections. I walked up the grey stone steps, leaving wet footprints.

I sat down next to my dad to figure it out on paper. “Why did you make the lengths between our pilotis thirteen feet?” I practiced pronouncing the French word correctly. “Isn’t thirteen bad luck?”

Implosion

Implosion